If you live in a community that is prone to wildfires, it’s important to know that devastating flooding and mudflows often follow wildland blazes.

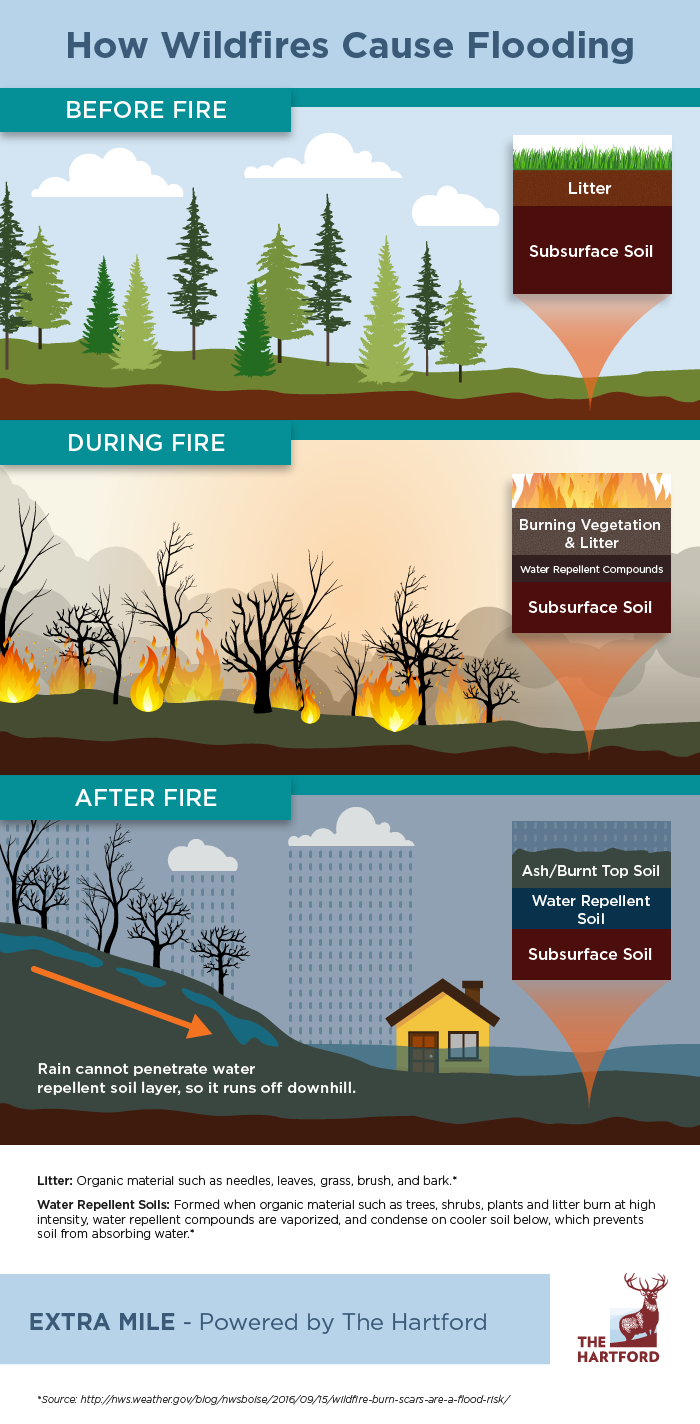

After a wildfire, the charred ground it leaves is far less able to absorb water. This greatly increases the risk of flash floods and mudflows during rainfall. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) describes this double threat from fire and floods as “a one-two punch.” Before residents can repair their fire-damaged homes, they often are hit with torrents of water or rivers of mud.

Burn scars, the scorched land that’s left behind after a wildfire has destroyed vegetation, are highly susceptible to flooding, since plants that once held in moisture are gone, explained Scott McLean, a deputy fire chief at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, also known as CAL FIRE. Homes and buildings located downhill or downstream from burn scars are in danger of flooding and mudslides until lost vegetation returns.

In Southern California, where fires have ravaged hundreds of thousands of acres since late 2017, many communities are in danger of mudflows and flooding. “This is our rainy season,” said Frank Mansell, a spokesman for FEMA. “That makes the areas that are burned very susceptible to flash flooding. The risk has not gone away. In fact, it has increased.”

What’s going on in California?

California’s weather in December was characterized by a lack of rain, dry vegetation, and strong Santa Ana winds. These conditions led to numerous wildfires across the southern portion of the state, reported the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Throughout the state, wildfires burned an area over 1,670,000 acres in 2018, according to CAL FIRE. The 2018 wildfire season was considered the most destructive wildfire season on record in California.

The danger of flooding can last for years.

According to the National Weather Service (NWS), the danger of flash floods, which can strike with little warning, is greatest during the first two years following a wildfire. This risk will remain elevated until natural vegetation can regrow, which may take up to five years, FEMA reports.

Burned areas with higher degrees of slope have an increased risk of flooding. Floods that occur on steep terrain often become debris flows, which consist of rushing water that can sweep away homes, cars, and vegetation.

How much rainfall is required to produce a flash flood after a wildfire?

The amount of rainfall needed to produce a flash flood following a wildfire varies widely, depending on the how much soil has been robbed of vegetation and the steepness of slopes, said Sean Scott, author of The Red Guide to Recovery, a handbook for disaster survivors.

Shaun Moise, president of a remediation company that responds to fire and water damage, said a flash flood can happen with less than an inch of rainfall after a wildfire. “A half an inch of rainfall in less than an hour can cause flash flooding in a burn area, depending on the severity of the fire and the slope of the hill,” he said.

How much time do I have to escape a flash flood?

When there has been severe burn damage, area residents may have very little time to evacuate to avoid a flash flood or mudslide. Authorities advise people in such communities to pay attention to weather reports.

Steep terrain combined with a burn scar and light precipitation can result in flash flooding within minutes of the start of rainfall. The length of time there will be an elevated risk of flash flooding and mudflows depends on the severity of the burn scar — that is, how badly the soil has eroded. Each area has unique risks for flash floods. These may include how close the burn scar is to population centers and the grade of the terrain.

How do I know when to evacuate?

It’s important to evacuate promptly whenever public safety officials advise you to do so, but you don’t have to wait for an official order. A good rule of thumb is to leave your home whenever you feel that your safety is threatened.

People who have evacuated one or more times in recent months may become complacent and decide not to leave when a new evacuation advisory is issued. This reluctance to go sometimes is called “evacuation fatigue,” and it’s understandable.

Evacuating a home is hard work. You have to quickly pack your most valued possessions and find an alternative place to live until the evacuation advisory is lifted. Sleeping on a cot in an evacuation center is no one’s idea of a good time. However, it’s important to remember that public safety authorities don’t issue evacuation orders unless the chance of your home’s being damaged by a fire or flood seems likely. The safest thing to do is leave when you are asked to do so.

How can I be prepared for flooding?

If you’re living in a burn scar area, there are things you can do to protect yourself from potential flash flooding, mudflows, and debris flows, said Mansell. The first step is to prepare for an evacuation. Don’t wait until an evacuation advisory is issued to start getting organized, he said. Have the things you plan to take with you ready to go.

“Preparedness includes such things as having a go-kit and having your car packed with survival supplies,” said Mansell.

A go-kit should contain important documents, such as insurance policies, deeds, wills, passports, and a home inventory of the possessions in your home, in case you have to file a claim with your insurance company. When creating your kit, try to think of all the important documents you’ll need if you can’t return home, said McLean.

When you pack a survival kit, CAL FIRE recommends that your supplies include such things as:

- A three-day supply of nonperishable food

- Three gallons of water for each person in your household

- A map showing at least two evacuation routes

- Prescription medications

- A change of clothing

- Extra eyeglasses or contact lenses

- Cash, credit cards, debit cards, or traveler’s checks

- A first aid kit

- A flashlight

- A battery-powered radio, so you can listen to news updates

McLean said another way to prepare yourself is to make sure that water can flow freely around your dwelling. That means clearing debris from any culverts or ravines that can help channel rainwater away from your residence. Other things you can do include:

- Making sure downspouts carry water away from your property to well-drained areas.

- Making sure your furnace and water heater are at least one foot above the floor.

- Securing fuel tanks on your property to make sure they aren’t dislodged by floodwaters.

- Making sure electrical components, such as switches and circuit breakers, are at least a foot above the anticipated flood line.

Do I need flood insurance?

If your community is prone to flooding, Mansell suggests that you consider buying flood insurance. Just an inch of water in an averaged-size home can cause more than $25,000 in damage, reports FEMA.

If you are the victim of a flooding situation, the actions you take in the first 24 hours after the flood are critical.

Scott warns that flood waters can become a dangerous toxic soup. “A lot of times you have raw sewage, dead animals, insecticides,” he said. If this toxic mix gets into your home, “the drywall and carpeting become breeding ground for pathogens, mold spores, and bacteria,” he added. “In most cases, you have to gut the house and start over.”

Standard homeowners insurance policies don’t protect against flood damage, said Mansell. You can buy flood insurance through an insurance agent or an insurer who takes part in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Costs are based on your property’s location and the flood risks. Be aware that there is a 30-day waiting period before most flood insurance policies take effect.

According to FEMA, the average cost of a flood policy is about $890 per year for homeowners. For dwellings within moderate- and low-risk areas, rates begin at under $516 per year.

In order to correctly identify your insurance needs, you also have to understand the differences between coverage for mudflow, mudslides, and landslides.

Here are the terms you need to know.

If you live in a community that’s threatened by flooding or mudslides following a wildfire, it’s helpful to be familiar with the following terms:

- Burn scar. When a wildfire burns away the vegetation, the barren soil that remains is called a burn scar. The charred soil repels water, preventing the earth from absorbing moisture. This can contribute to flooding.

- Debris flow. A debris flow is a moving mass of mud, sand, soil, rock, and water that is carried down a slope. It can happen with little or no warning and travel at avalanche speeds, growing in size as it picks pick up trees, boulders, cars, and other objects in its path. Debris flows are also known as mudslides.

- Flash flood. Most flood deaths are due to flash floods, which often occur with little or no warning, according to the National Weather Service. They can happen within a few minutes or hours of excessive rainfall or dam failures. Flash floods are powerful enough to move boulders, topple trees, or collapse homes. The rushing water can reach heights greater than 30 feet.

- Mudflow. A mudflow is a river of liquid and flowing mud. The main ingredient is water. Mudflows don’t carry large objects, such as trees or rocks, and they aren’t covered by standard homeowners insurance policies. They are covered by flood insurance policies.

Which states are at greatest risk from wildfire hazards?

More than two million homes in California are considered at high or extreme risk from wildfires and the floods that often follow. That makes it the state with the highest wildfire risk, according to Verisk, a data analytics firm. After California, the state with the most households at risk from wildfires is Texas, followed by Colorado, Arizona, Idaho, Washington, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, and Montana.

Scott said the reason why wildfires are becoming more common is that as communities are built out, housing developers are pushing deeper into the wildlands along the fringe of urban areas. Such neighborhoods are located near dense vegetation, which fuels fires during hot and windy weather.

“People are moving further and further out into the wildland interface and they are more exposed than ever,” he said.

Read More: Are Flooding Risks on the Rise?